They went into the muslin bags easily as we freed them one by one from under the heavy net. Some were stunned, frozen, immobile; others struggled between the strands, exploding with powerful wings when handled. I was a tag-along, a newbie, an invited guest to this fall ritual of trapping, counting, banding, and collaring Aleutian cackling geese (Branta hutchinsii leucopareia), an annual joint venture between the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW). My fellow banders included CDFW biologists, USFWS employees, and an assortment of volunteers and fire personnel. They worked quickly in the fading light, retrieving birds and inserting them carefully into the bags—temporary holding quarters that both calmed and kept the birds safe until they could be individually retrieved and processed—which involved examining each bird to determine its age and sex, and attaching a metal leg band and neck collar. The collar, blue with a white three-digit code, was the primary reason for conducting the operation. Biologists use the collar numbers to keep track of the geese in the field in subsequent years in order to estimate population numbers.

Photo Courtesy of Erin Johnson

Aleutian cackling geese are an Endangered Species Act success story, a species that came close to extinction when they became the unintended collateral damage of a century of fur-trapping in the Aleutian Islands. They were saved by a successful recovery program that included simultaneous protection from an introduced predator to their Aleutian Island breeding grounds, the Arctic fox, and restoration of their winter feeding habitat in California’s Central Valley.

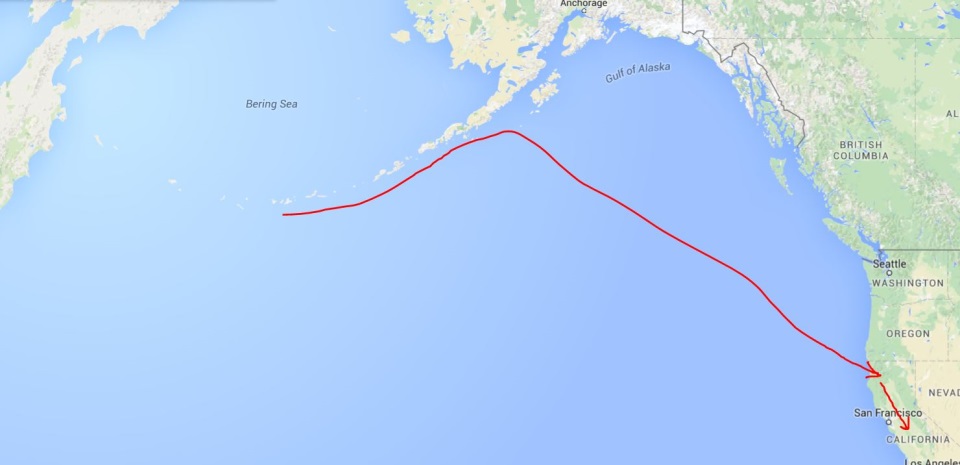

The yearly migration of Aleutian cackling geese is an amazing story itself: these diminutive white-cheeked birds must fly 2,500 miles from the Aleutian Islands across the open Pacific Ocean before making landfall in far northeastern California. From there the majority of the migrating geese make their way south to the northern San Joaquin Valley. Their core winter range includes the San Joaquin River National Wildlife Refuge and the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, where they feed in grain fields and rest in wetlands. Come late winter and early spring, the geese reverse their journey, stopping again to feed in Humboldt and Del Norte County pastures to fuel their long migration north.

Photo Courtesy of Erin Johnson

Our bagging and collaring operation takes place on the refuge. We lay the bagged geese in the shadow of a pick-up truck where two CDFW biologists sit on overturned buckets and determine the sex and age class—adult or juvenile—of each bird before they are banded and collared. A biologist hands me my bird, and I carry him carefully—an adult male—to the tailgate of the pickup where another biologist attaches a band. A third volunteer records the age and sex, and a last volunteer encircles its neck with a bright blue collar sporting a visible white combination of numbers and letters that can easily be seen through spotting scopes and binoculars. There will be no need to capture this bird again.

Photo Courtesy of Erin Johnson

Once my bird is banded, tallied, and collared, I walk away from the truck into the quiet of the mowed field, holding my bundle tightly for another 30 seconds or so until the glue on the collar has dried. I can feel the power of its feathery body against my chest and its racing heart under my hands. We stand there in the deepening evening, the Aleutian cackler and me, two sentient beings bound together for a short 10 minutes by his happenstance netting. I adjust my hold on him, binding the wings more tightly with one hand as I run my fingers under the collar to assure that it’s free of neck feathers. Then I carefully set him on the ground and watch thoughtfully as he runs a few yards and launches gracefully into the air. In another minute, he is gone into the dark night sky.