I live in the heart of wildness. Literally. The cabin in which our family has lived for the past twenty years lies roughly in the center of the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem, arguably one of the wildest intact ecosystems south of Alaska. Getting to know this vast landscape, where mountains and public lands stretch from horizon to horizon, sparked my interest in corridor ecology—the science of how animals move across landscapes and inhabit them. I wanted to better understand the conservation requirements of animals that need to cover a lot of ground in order to thrive, and what people can do to create healthier, more connected landscapes for them.

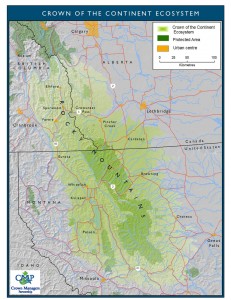

The Crown of the Continent Ecosystem covers 28 million acres and extends east to where the Great Plains meet the Rocky Mountains, south to Montana’s Blackfoot River Valley, west to the Salish Mountains, and north to Alberta’s Highwood Pass. The Continental Divide splits it north to south. Its jumbled terrain contains a crazy quilt of mountains: the Livingstone, Mission, and Whitefish ranges, among many. Watersheds best characterize this ecosystem: the Elk, Flathead, Belly River, and Blackfoot. It contains a triple divide peak from which rainfall flows into the Pacific, Arctic, and Atlantic oceans, and thousands of lakes of glacial origin. But anyone who’s spent time here knows the Crown of the Continent is far more than the sum of its parts, its wildness seemingly endless.

The large carnivores are part of what makes this place so ecologically remarkable. One of the two ecosystems in the forty-eight contiguous United States that contain all the wildlife species present at the time of the Lewis and Clark expedition (1804-1806), the Crown of the Continent provides critical habitat for animals that need room to roam. John Weaver, senior scientist for the Wildlife Conservation Society, has found seventeen carnivore species here, a number unmatched elsewhere in North America, including in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and Alaska.

According to Weaver, the Crown of the Continent matters for three principal reasons. First, because of its large, intact wildlands that provide habitat security for carnivores compared to other ecosystems with greater human development. Second, because of its connection to northern ecosystems with abundant large carnivores. Third, because of its physical and biological diversity. The Crown of the Continent has four climatic influences: Pacific Maritime in the west, prairie in the east, boreal in the north, and Great Basin in the southwest. Coupled with a tremendous range of elevation from prairie to peak, these influences support a variety of ecological communities, from shortgrass prairie to old-growth rainforest.

Within this ecosystem, rivers have incised narrow, fertile valleys, which represent the last bastions of wildness, where a grizzly bear can travel easily, finding abundant food and little trace of humanity. I live in one of these valleys, in a place where the large carnivore population outnumbers the human population. Yet much is at stake, even in a place as wild as this. For example, some of these animals are having their travel corridors cut off by logging, natural gas extraction, and backcountry recreation (e.g., use of snowmobiles).

Lynx using a wildlife overpass over Highway 1 in Banff national Park Photo credit: Anthony Clevenger.

Today, Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y), Crown Managers Partnership, Wildlands Network, Headwaters Montana, and other organizations are helping keep the Crown of the Continent wild and connected. In the weeks to come I will be posting stories about some of their efforts, which include wildlife overpasses that enable grizzly bears, wolverines, lynx, and wolves to cross busy highways safely, and epic treks by conservation leaders Karsten Heuer in the 1990s and Island Press author John Davis in 2013.

To learn more about the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem and the importance of keeping it wild and connected, I recommend John Weaver’s Wildlife Conservation Society reports and the recently published book, Crown of the Continent: The Wildest Rockies by Steven Gnam, which contains Gnam’s evocative photographs and essays by Douglas Chadwick and Michael Jameson.

Lynx using a wildlife overpass over Highway 1 in Banff national Park Photo credit: Anthony Clevenger.

Today, Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y), Crown Managers Partnership, Wildlands Network, Headwaters Montana, and other organizations are helping keep the Crown of the Continent wild and connected. In the weeks to come I will be posting stories about some of their efforts, which include wildlife overpasses that enable grizzly bears, wolverines, lynx, and wolves to cross busy highways safely, and epic treks by conservation leaders Karsten Heuer in the 1990s and Island Press author John Davis in 2013.

To learn more about the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem and the importance of keeping it wild and connected, I recommend John Weaver’s Wildlife Conservation Society reports and the recently published book, Crown of the Continent: The Wildest Rockies by Steven Gnam, which contains Gnam’s evocative photographs and essays by Douglas Chadwick and Michael Jameson.

Lynx using a wildlife overpass over Highway 1 in Banff national Park Photo credit: Anthony Clevenger.

Lynx using a wildlife overpass over Highway 1 in Banff national Park Photo credit: Anthony Clevenger.