With more and more cases of Zika virus being reported, some experts are calling for the use of DDT to combat the mosquitoes that transmit it. We asked Emily Monosson, author of Unnatural Selection and Evolution in a Toxic World to weigh in on the proposed use of pesticides, and what else we can do to protect ourselves from disease-carrying insects.

Over the past fifteen years I’ve experienced the spread of Lyme disease in my own backyard. Within a matter of years, the field where my daughter used to unpack her little wicker basket—laying out a blue-checked table cloth and two teacups painted with images of Winnie-the-Poo and Eeyore—has transformed from a field of emerald green grass and wildflowers to a danger-zone where the consequence of a Sunday afternoon tea-party may be a bout with Lyme.

In little over a decade, the Lyme bacterium, the deer ticks, the white-footed mouse, and deer that host the ticks have all become more prevalent. This is our new reality. Human-induced change from altered habitats, reductions in predators, and a warming climate are enabling pest and pathogen to move into new spaces. And Lyme is a harbinger of things to come.

Mosquitoes, along with their disease-causing hitchhikers like West Nile, Equine encephalitis, Dengue, and now Zika, are on the move, finding new habitats and naïve populations ripe for infection. Just as Lyme has made tick experts out of us all (no, that one is just a dog tick), we are on a first-name basis with mosquitoes like Aedes and Culex. Here in the Northeast dozens of mosquito varieties bite, buzz, and mate. Some inject pathogens, most don’t. Each has their own preferences and habits. Culex pipiens carries West Nile and favors biting birds to humans; Coquillettidia perturbans is a midsummer’s carrier of Eastern Equine Encephalitis and feeds upon anyone and everyone from birds to humans; Ochlerotatus sticticus is another daytime disease carrying biter. Others prefer non-human mammals, or frogs, or even snakes. In Massachusetts alone there are over fifty varieties of mosquitoes. Of all disease-carrying insects, mosquitoes are the hands-down winners as the world’s greatest menace. But, of the thousands of known varieties worldwide, only a few hundred bite humans, and fewer transmit disease. Then again, it only takes one.

The Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, is a relative newcomer to the Northeast. First identified nearly 30 years ago in a Texas dump, the aggressive blood-sucker, likely aided by a warming climate, has marched northward over the decades. Known to transmit as many as twenty different kinds of pathogens in different regions around the globe, health experts fear that someday soon the tigers will be delivering pathogens like Dengue, chikungunya, or Zika to more northern regions of the U.S.

The Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus is known to transmit as many as twenty different kinds of pathogens in different regions around the globe, including the United States. By James Gathany/CDC, via Wikimedia Commons

Zika and Dengue are also transmitted by Aedes aegypti. Warmer-weather mosquitos which, like the tiger, are particularly well adapted for life amongst humans with a penchant for laying their eggs in roadside bottle-caps, abandoned tires, or backyard tarps. A habit that makes them particularly successful breeders—free from natural predators like fish or dragonfly larvae—and difficult to eradicate with pesticide spray programs. Centuries ago, yellow fever outbreaks in Northeast cities from Boston to Philadelphia suggest that Aedes, likely carried aboard ship from far-flung ports, survived long enough to spread disease before succumbing to cool weather. While these beasts of the subtropical wilds haven’t yet made a go of it in the north, climate change may alter that.

Those of us who remember mosquito-free evenings of the 60s and 70s probably also remember the fog of DDT trucks. With the advent of synthetic chemistry, we turned to miraculous chemical cures like DDT and other powerful pesticides. It seemed there wasn’t a pest we couldn’t conquer. A few decades later our hubris was rewarded with a catastrophic decline in raptors and resistance in targeted insects. Plenty of communities still spray next-generation pesticides (like resmethrin and biologically-based bacterial sprays) but for every chemical cure there is, or will likely soon be, a resistant population. Pests with amped up detoxification systems or target sites with reduced sensitivity. Not to mention harm done to the innocent bystanders, beneficial insects that prey upon pests or pollinate plants. And, for a species like Aedes, pesticide from a large-scale spray program may not find its way into that bottle cap, or dog bowl or old tire. For these buggers, control requires a more personal touch: a weekly scan of the yard, junk yard, or parking lot. With a flight range of a couple hundred meters, clearing a yard or a neighborhood block of mosquito breeders can go a long way towards control.

So far, mosquitos carrying Zika haven’t yet been reported in the continental U.S.; though it is likely only a matter of time. And if it’s not Zika, some other mosquito-borne virus will be coming to our neighborhoods someday soon.

There is some hope. Most notably, scientists have engineered mosquitoes to produce offspring destined to die before they are old enough to reproduce. This strategy is already in trials in Brazil, Florida, and elsewhere. Because reproduction is the Achilles heel of the evolutionary process (inheritance, inheritance, inheritance!), it is a strategy unlikely to be circumvented by evolved populations. And while we have learned time and again that it is difficult to fool Mother Nature, we also need to consider the consequences of actually doing so. Like, the consequences of world without Aedes or other mosquitoes. Most ecologists aren’t too concerned. Predators that feed on mosquitoes or larvae will find other food; other pollinators will fill in where mosquitoes left off. But the end of mosquitoes isn’t in our near future; at best the strategy may work on localized populations or regionally rather than going global.

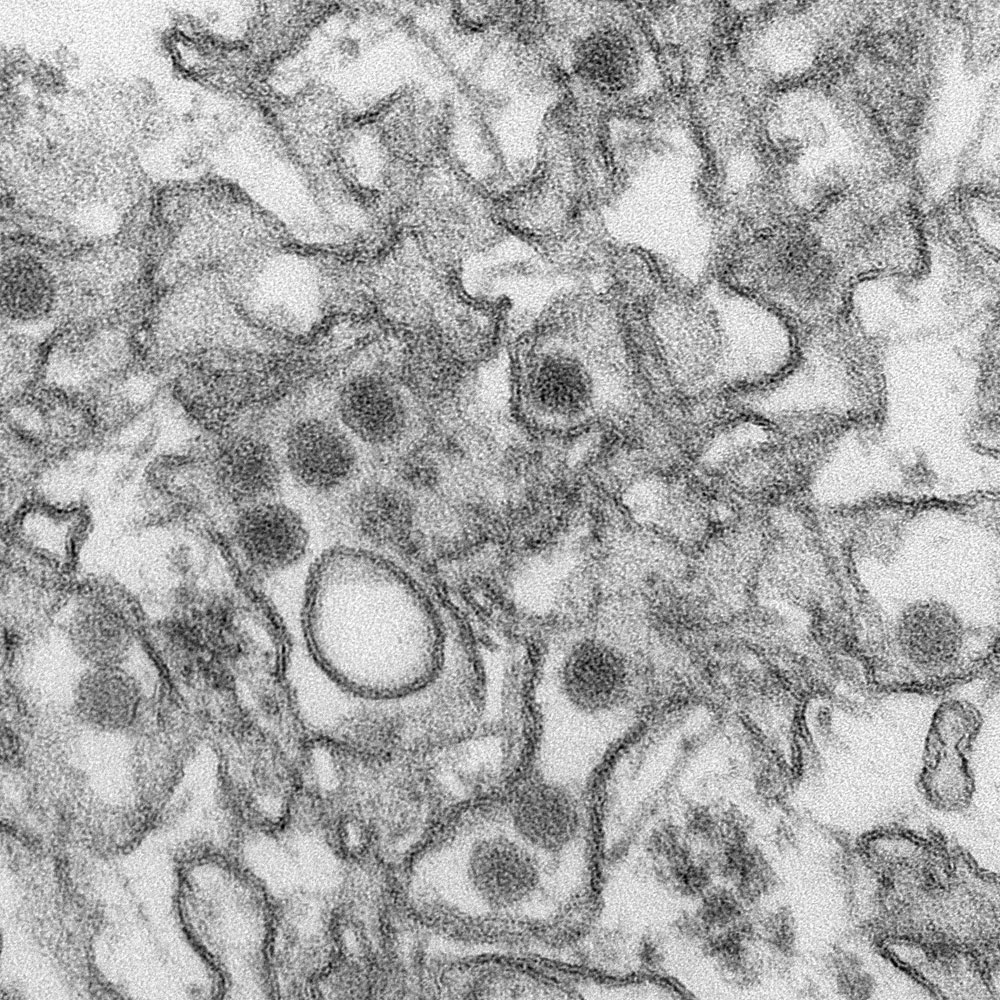

Transmission electron micrograph of Zika virus. By CDC/Cynthia Goldsmith, via Wikimedia Commons

On the flip side, if we can’t stop the pest, perhaps we can stop the pathogen. Mosquito-borne diseases have killed hundreds of millions of people (approximately one million individuals each year). Vaccines have saved many more. There aren’t yet vaccines for West Nile and chikungunya (though a vaccine for Dengue, twenty years in development, just became available in some countries), and of course Zika is prompting vaccine developers to scramble, promising accelerated vaccine development and production. Even so, it may be years before vaccines enable us to shed our long sleeves and ditch the mosquito repellent.

So what are our options? After nearly a century of resting on our chemical laurels, we need to think differently. There is no quick fix. As with Lyme we will all need to become a little more wary, a lot less cavalier and a bit more humbled by Nature. We will need to be more strategic about how and when we use pesticides, how we dress when we go outside, and perhaps even when we go outside. We also need to be more aware of our contribution to the problem. But that doesn’t mean we need to cloister ourselves indoors.

When we venture out into the field during tick season (a depressingly longer stretch of time each year), we expect ticks. Years ago we joked about “tick-checks.” Now they are a part of the daily routine. We scoffed at “birding couture:” the long sleeves, light clothing, pants tucked into socks. Not so now. Maybe it’s time to dig out that bug head net I bought for gardening but never wore. Not so comfortable, but what the heck. And sweeping around the yard every few days drying out the mosquito breeders will definitely become part of the spring and summer routine. As much as I know not to leave standing water, the dog bowl has nurtured plenty of newly hatched mosquitos over the years. With our ever-changing world, we don’t have to live in fear, but we do need to live more aware.