Booklist called it a "must-read." Kirkus deemed it a "hard-hitting, eye-opening narrative." To Publishers Weekly it is "a damning picture." Carey Gillam's Whitewash uncovers one of the most controversial stories in the history of food and agriculture at a time when a new political administration has set about slashing regulations of pesticides. We sat down with Carey to speak about power, politics, and the deadly consequences of putting corporate interests ahead of public safety. Read that conversation, and share your questions in the comments, below.

You’ve been reporting on pesticides and Monsanto for nearly 20 years. As a journalist, why was it important to write a book about the topic? Why now?

Health experts around the world recognize that pesticides are a big contributor to a range of health problems suffered by people of all ages, but a handful of very powerful and influential corporations have convinced policy makers that the risks to human and environmental health are well worth the rewards that these chemicals bring in terms of fighting weeds, bugs, or plant diseases. These corporations are consolidating and becoming ever more powerful, and are using their influence to push higher and higher levels of many dangerous pesticides into our lives, including into our food system. We have lost a much-needed sense of caution surrounding these chemicals, and Monsanto’s efforts to promote increased uses of glyphosate is one of the best examples of how this corporate pursuit of profits has taken priority over protection of the public.

People may not be familiar with the term “glyphosate” or even “Roundup.” What is it? Why should people care?

Roundup herbicide is Monsanto’s claim to fame. Well before it brought genetically engineered crops to market, Monsanto was making and selling Roundup weed killer. Glyphosate is the active ingredient—the stuff that actually kills the weeds—in Roundup. Glyphosate is also now used in hundreds of other products that are routinely applied to farm fields, lawns and gardens, golf courses, parks, and playgrounds. The trouble is that it’s not nearly as safe as Monsanto has maintained, and decades of scientific research link it to a range of diseases, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

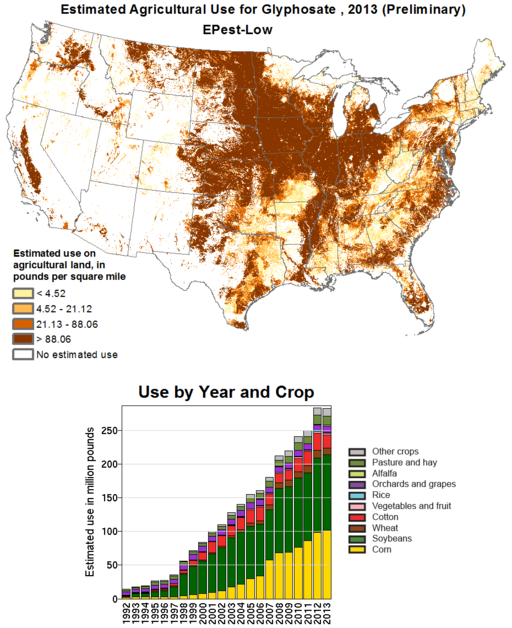

Monsanto has known about these risks and worked very hard to hide them while promoting more and more use. Monsanto’s genetically engineered crops are all built to encourage glyphosate use. The key genetic trait Monsanto has inserted into its GMO soybeans, corn, canola, sugar beets, and other crops is a trait that allows those crops to survive being sprayed directly with glyphosate. After Monsanto introduced these “glyphosate-tolerant” crops in the mid-1990s, glyphosate use skyrocketed. Like other pesticides used in food production, glyphosate residues are commonly found in food, including cereals, snacks, honey, bread, and other products.

You write that Whitewash shows we’ve forgotten the lessons of Rachel Carson and Silent Spring. What do you mean by that?

Carson laid out the harms associated with indiscriminate use of synthetic pesticides, and she predicted the devastation they could and would bring to our ecosystems. She also accused the chemical industry of intentionally spreading disinformation about their products. Her book was a wake-up call that spurred an environmental movement and led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. But over the decades since, the general population and certainly our politicians and regulators have clearly forgotten the need for caution and scrutiny in dealing with these pesticides and the companies that profit from them. You see a push by our political leaders for fewer regulations, for more unchecked use of glyphosate and other pesticides in our food production, while research about how these pesticides cause cancer, how they harm children’s brain development, and how they alter reproductive health all get pushed aside.

You obtained industry communications and regulatory documents that reveal evidence of corporate influence in regulatory agencies like the EPA. Does the evidence you uncovered take on new significance in light of the current political climate in the US? How can people keep regulatory agencies accountable for working in the public’s best interest?

Yes, it’s quite clear that Monsanto and other corporate giants like Dow Chemical enjoy significant sway with regulators, the very people who are supposed to be protecting the public. The companies use their money and political power to influence regulatory decision-making as well as the scientific assessments within the regulatory agencies. If we consumers and taxpayers want to protect our children, our families, our future, we need to pay attention, educate ourselves on these issues, write and call our lawmakers, and support organizations working on our behalf to protect our health and environment. We need to be proactive on policies that protect the public, not the profits of giant corporations. Capitalism is great—the pursuit of wealth through a free marketplace provides much that is good, that is true. But when we let corporate profit agendas take precedence over the health and well-being of our people and our planet we’re sacrificing far too much.

Monsanto attempted to censor and discredit you when you published stories that contradicted their business interests. What strategies can journalists—or scientists—employ when faced with this pushback? What are the stakes if they don’t?

Monsanto, and organizations backed by Monsanto, have certainly worked to undermine my work for many years. But I’m not alone; they’ve gone after reporters from an array of major news outlets, including the New York Times, as well as scientists, academics, and others who delve too deeply into the secrets they want to keep hidden. I see it as a badge of honor that Monsanto and others in the chemical industry feel threatened enough by our work to attack us. It’s certainly not easy, for journalists in particular, to challenge the corporate propaganda machine.

Reporters that go along with the game, repeat the talking points, and publish stories that support corporate interests are rewarded with coveted access to top executives and handed “exclusive” stories about new products or new strategies, all of which score them bonus points with editors. In contrast, reporters who go against the grain, who report on unflattering research, or who point out failures or risks of certain products often find they lose access to key corporate executives. The competition gets credit for interviews with top corporate chieftains while reporters who don’t play the game see their journalistic skills attacked and insulted and become the subject of persistent complaints by the corporate interests to their editors.

What can be done? Editors and reporters alike need to check their backbones, realize that the job of a journalist is to find the story behind the spin, to ask uncomfortable questions and to forge an allegiance only to truth and transparency. When we lose truthful independent journalism, when we’re only hearing what the powerful want heard, it’s assured that those without power will be the ones paying the price.

You interviewed a huge number of people for this book, including scientists, farmers, and regulators. Is there a particular conversation or story that stands out to you?

I’ve interviewed thousands of people over my career, from very big-name political types to celebrities to every day men and women, and I find it’s always those who are most unassuming, those “regular folk” who grab my heart. In researching this book, the individual story that most resonated with me is that of Teri McCall, whose husband Jack suffered horribly before dying of cancer the day after Christmas in 2015. The McCall family lived a quiet and rather simple life, raising avocadoes and assorted citrus fruits on their Cambria, California farm, using no pesticides other than Roundup in their orchards. Jacks’ death from non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a type of cancer linked to glyphosate, fully devastated Teri and her children and grandchildren. She has shown so much grace and strength and she gave me so much of her time—and her tears—in telling me Jack’s story. She is a woman I truly admire.

Of course there are so many others I have learned from, who I feel for, including the scientists who have struggled to publish research, who have been censored or worse for their findings of harm associated with glyphosate and other pesticides. And farmers—I have so much regard for farmers generally, including each and every one interviewed for this book. The work they do to raise our food is incredibly challenging and they are on the front lines of the pesticide dangers every day.

You’ve been immersed in this topic for years. Was there anything you found in the course of researching and writing this book that surprised you?

Jaw-dropping is the best way to describe some of the documents I and others have uncovered. Seeing behind the curtain, reading in their own words how corporate agents worked intentionally to manipulate science, to mislead consumers and politicians, was shocking. As a long-time journalist, I’m a bit of a hardened cynic. Still, the depth of the deception laid bare in these documents, and other documents still coming to light, is incredible.

What do you hope readers take away from Whitewash?

A writer at the New York Times told me after reading Whitewash that she feared eating anything in her refrigerator because of the information the book provides about the range of pesticide residues found in so many food products. That definitely is not my goal, to frustrate or frighten people. But I do hope that readers will be moved to care more about how our food is produced, how we make use of dangerous synthetic pesticides not just on farms but also on schoolyards and in parks where our children play.

And I hope they will want to be engaged in the larger discussion and debate about how we build a future that adequately balances the risks and rewards associated with these pesticides. As Whitewash shows, the current system is designed to pump up corporate profits much more than it is to promote long-term environmental and food production sustainability. There are many powerful forces at work to keep the status quo, to continue to push dangerous pesticides, almost literally down our throats. It’s up to the rest of us to push back.