Most people now accept that the world’s climate is changing rapidly as a result of human activities — mainly the direct emissions of carbon dioxide and other gases that trap heat radiating from the earth, causing the temperature of our small blue planet to rise. This is leading to all sorts of political, economic and ecological problems.

The effects of climate change caused by rising global temperatures are increasingly well documented, and we know what we need to do to slow the process (halting it is, unfortunately, impossible in the foreseeable future) enough to give us, and the world’s ecosystems, time to adapt to it. The actions needed involve difficult decisions and changes that will affect our social and economic systems. The whole business is made more difficult by the fact that there are people — and politicians seem to be well represented in this group — who do not accept the reality of climate change.

Things are changing in this respect. Around the world there is widespread acceptance that climate change is real and serious, and of the fact that human activities are responsible for the speed at which it’s happening. However, we have just seen the election as (prospective) president of the United States, of a man who says climate change is a hoax, so it’s clear that the battle to convince as many people as possible of the reality and seriousness of the problem must go on. It seems that the best political outcome would be to persuade governments to tax carbon emissions. This would have all sorts of benefits for the economies of the countries that do it, as well as being the most effective measure anyone has thought of to check, and reduce, emissions while speeding the switch to more sustainable energy sources.

The concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 6, 2012

The economic and ecological problems created by climate change include rising sea levels, more frequent and severe droughts, affecting food production in some parts of the world, and more frequent severe weather – storms, floods and heat waves. Natural ecosystems such as forests are subject to increasingly frequent disease and insect attacks as well as severe fires. But, besides being strongly affected by climate change, forests have an important role in mitigating it.

As scientists we have long been concerned with the general health and productivity of forests, with how to manage them to deal with the impacts of climate change and how forest management can help mitigate the problem.

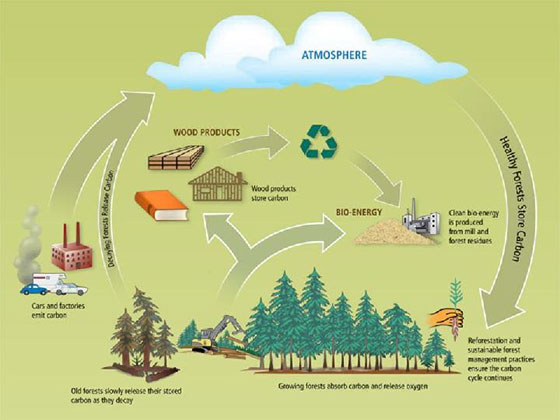

Forests are huge sponges (or sinks) for carbon dioxide. Trees grow by absorbing CO2 and using the sun’s energy to turn the gas into carbohydrates—wood.

It has been estimated that forests fix, annually, about 60% of the emissions from fossil fuel burning and cement making — the latter a very large source of CO2. Young, actively-growing forests fix more CO2 than mature forests (although mature forests store more carbon). The bad news is that almost all the carbon fixed annually by forests is returned to the atmosphere by deforestation and burning. These statistics tell us that any management practice which increases (or just sustains) the growth rate of forests increases the amount of CO2 they take out of the atmosphere each year, while reducing deforestation rates will reduce the rate of accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere.

We mentioned earlier that climate change is making some forests more susceptible to disease and insect attack. Trees stressed by high temperatures and drought are less resistant to such attacks than healthy, unstressed trees. If a high proportion of the trees in a stand are killed, the stand becomes nothing more than a fire-storm waiting to happen. In the past year, across the western US, in Australia and Canada and Europe, these firestorms have happened quite frequently, with massive impacts on people and economies as well as regional ecosystems.

We can’t do anything about the high temperatures and droughts in particular areas, but forest management practices such as thinning which, in effect, makes more of the water in the soil available to the remaining trees, help keep stands vigorous and healthy and more resistant to disease and insect attack. Prescribed ‘cool’ burns, carried out when the forests are not dry enough for the fires to explode into out-of-control wildfires, offer another approach.

Photograph by R.H. Waring. Related blog here.

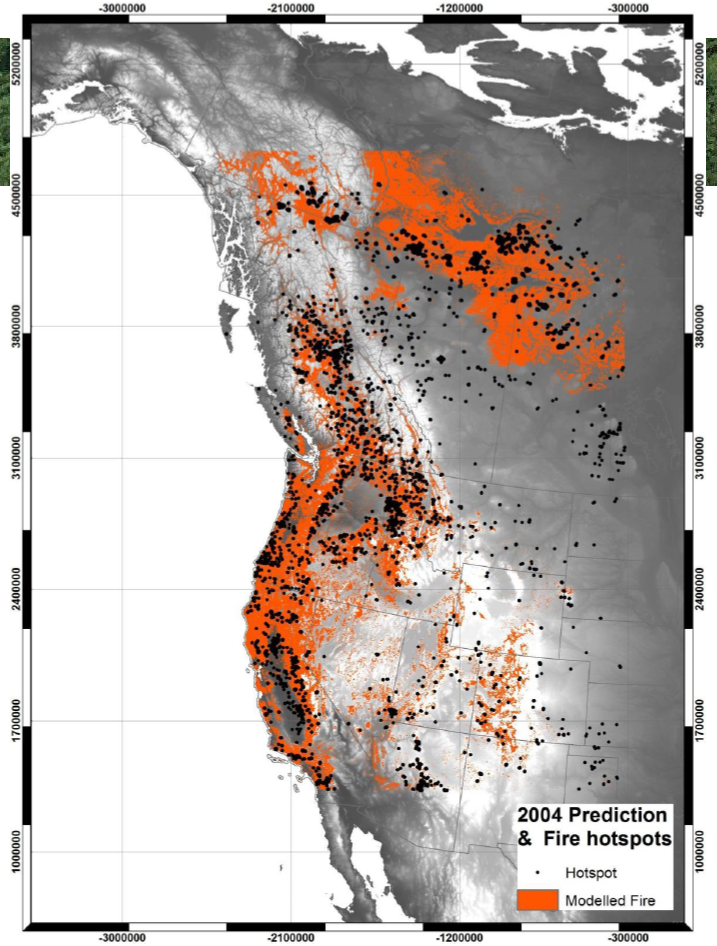

We have remote sensing tools, now, that allow us to monitor forests from space. We can detect and quantify the illegal logging, rampant in many parts of South America, in Indonesia and other Asian countries, and so bring pressure on those countries to curb the practice. We have developed models that use observations made by satellites, with weather data and information about soils, to predict forest growth and rates of carbon sequestration, by forests around the world. Models are also available that can predict when and where forests are most susceptible to fire, insects, and disease. We can use these, with data acquired from satellites, to assess the effectiveness of global management and plan how to improve it.

It may be that the battle against climate change cannot be won— at least, it seems unlikely that hopes for keeping average temperature changes to 2oC or less will be realized. That being the case, as well as continued efforts to restrain and reduce our carbon emissions, we have to learn to manage the situation in which the world finds itself. Resilience — the capacity to bounce back, to recover or to find a new acceptable route — has to be the operative word. For a resilient world we need very large areas of healthy forests.