Our Renewable Future

Laying the Path for One Hundred Percent Clean Energy

248 pages

6 x 9

14 photos, 33 illustrations

248 pages

6 x 9

14 photos, 33 illustrations

One of GreenBiz's Six Best Sustainability Books of 2016

The next few decades will see a profound energy transformation throughout the world. By the end of the century (and perhaps sooner), we will shift from fossil fuel dependence to rely primarily on renewable sources like solar, wind, biomass, and geothermal power. Driven by the need to avert catastrophic climate change and by the depletion of easily accessible oil, coal, and natural gas, this transformation will entail a major shift in how we live. What might a 100% renewable future look like? Which technologies will play a crucial role in our energy future? What challenges will we face in this transition? And how can we make sure our new system is just and equitable?

In Our Renewable Future, energy expert Richard Heinberg and scientist David Fridley explore the challenges and opportunities presented by the shift to renewable energy. Beginning with a comprehensive overview of our current energy system, the authors survey issues of energy supply and demand in key sectors of the economy, including electricity generation, transportation, buildings, and manufacturing. In their detailed review of each sector, the authors examine the most crucial challenges we face, from intermittency in fuel sources to energy storage and grid redesign. The book concludes with a discussion of energy and equity and a summary of key lessons and steps forward at the individual, community, and national level.

The transition to clean energy will not be a simple matter of replacing coal with wind power or oil with solar; it will require us to adapt our energy usage as dramatically as we adapt our energy sources. Our Renewable Future is a clear-eyed and urgent guide to this transformation that will be a crucial resource for policymakers and energy activists.

"A fascinating look at some of the ways our energy future may play out—and a reminder that every day we delay getting serious about climate change will make the eventual reckoning that much more difficult."

Bill McKibben, author of "Deep Economy"

"Without a doubt the most sensible book...on the prospects and promise of renewable energy."

Energy blog

"The future of renewable energy is obscured by ignorance, noise, ideology, and all sorts of misconceptions —from both cornucopians and catastrophists. Our Renewable Future describes the reality: the transition is possible, but it won’t be easy."

Ugo Bardi, University of Florence and The Club of Rome

Acknowledgements

List of Figures and Tables

Introduction

-How “normal” came to be

-Why a renewable world will be different

-Overview of this book

PART I. The Context: It’s All About Energy

Chapter 1. Energy 101

-What is energy? The basics of the basics.

-Laws of Thermodynamics

-Net energy

-Lifecycle impacts

-Operational versus embodied energy

-Energy resource criteria

Chapter 2. A Quick Look At Our Current Energy System

-Growth

-Energy rich, energy poor

-Energy resources

-End use

PART II. Energy Supply in a Renewable World: Opportunities and Challenges

Chapter 3. Renewable Electricity: Falling Costs, Variability, and Scaling Challenges

-Price is less of a barrier

-Intermittency

-Storage

-Grid redesign

-Demand management

-Capacity redundancy

-Scaling challenges

-Lessons from Spain and Germany

-Pushback against wind and solar

Chapter 4. Transportation: The Substitution Challenge

-Electrification

-Biofuels

-Hydrogen

-Natural gas

-Sails and kites

-Summary: A less mobile all-renewable future

Chapter 5. Other Uses of Fossil Fuels: the Substitution Challenge Continues

-High temperature heat for industrial processes

-Low-temperature heat

-Fossil fuels for plastics, chemicals, and other materials

-Summary: Where’s our stuff?

Chapter 6. Energy Supply: How Much Will We Have? How Much Will We Need?

-EROEI of renewables

-Building solar and wind with solar and wind

-Investment requirements

-The efficiency opportunity: We may not need as much energy

-Energy Intensity

-The role of curtailment and the problem of economic growth

Chapter 7. What About…?

-Nuclear power

-Carbon capture and storage

-Massive technology improvements

PART III. Preparing For Our Renewable Future

Chapter 8. Energy and Justice

-Energy and equity in the least industrialized countries

-Energy and equity in rapidly industrializing nations

-Energy and equity in highly industrialized countries

-Policy frameworks for enhancing justice while cutting carbon

Chapter 9. What Government Can Do

-Support for an overall switch from fossil fuels to renewable energy

-Support for research and development of ways to use renewables to power more industrial processes and transport

-Conservation of fossil fuels for essential purposes

-Support for energy conservation in general—efficiency and curtailment

-Better greenhouse gas accounting

Chapter 10. What We the People Can Do

-Individuals and households

-Communities

-Climate and environmental groups, and their funders

Chapter 11. What We Learned

-We really need a plan; no, lots of them

-Scale is the biggest challenge

-It’s not all about solar and wind

-We must begin pre-adapting to having less energy

-Consumerism is a problem, not a solution

-Population growth makes everything harder

-Fossil fuels are too valuable to allocate solely by the market

-Everything is connected

-This really does change everything

About the Authors

Several of the country’s leading energy analysts and environmental organizations have formulated plans for transitioning to 100% renewable energy. The fascinating new book, Our Renewable Future, gathers and assesses the viability of those plans. Join the book's authors leading scientists and thinkers in their own right, to explore the future of clean energy and how a fully renewable energy supply will shape our lives and economy. More details here.

The JP Forum is thrilled to welcome back Richard Heinberg, one of the world’s foremost experts on energy policy and community resilience. Join us for this special morning with Richard and members of the New England Resilience & Transition Network. Richard’s talk will kick off a day-long gathering of activists and organizers from around the New England region, folks building resilient local communities and resisting fossil fuel infrastructure. Richard’s new book, Our Renewable Future, will be available for purchase. More details here.

Modern economies--and the lifestyles and livelihoods of many of their citizens-- rely heavily on consumerism. Consumerism, in turn, relies heavily on energy--mostly in the form of fossil fuels. So what will consumerism look like after fossil fuels? Join Annie Leonard and John de Graaf for a lively, free-flowing conversation about what the future of consumerism might look like in a 100% renewable energy future. More details here.

Since our current food system is so heavily dependent on fossil fuels, major changes to agriculture, farm labor, food processing, food transport, and food packaging are likely as we move toward the renewable future. The transition to 100% renewable energy thus raises some profound questions for the future of our food system. Join Michael Bomford of the Sustainable Agriculture & Food Systems program of Kwantlen Polytechnic University and Tom Philpott of Mother Jones for a rich, thought-provoking conversation about what the future of food might look like in a 100% renewable energy future. Hosted by Asher Miller from Post Carbon Institute. More details here.

The next few decades will see a profound energy transformation throughout the world. By the end of the century (and perhaps sooner), we will shift from fossil fuel dependence to rely primarily on renewable sources – solar, wind, biomass, and geothermal power. Driven by the need to avert catastrophic climate change and by the depletion of easily accessible oil, coal, and natural gas, this transformation will entail a major shift in how we live. What might a 100% renewable future look like? Which technologies will play a crucial role in our energy future? What challenges will we face in this transition? And how can we make sure our new system is just and equitable?

Join energy experts Richard Heinberg and David Fridley, authors of the new book Our Renewable Future, for a discussion about the challenges and opportunities presented by the shift to renewable energy.

We use enormous amounts of energy to build, inhabit, and move around our communities—and most of that energy still comes from fossil fuels. Join us for a conversation with three long-time national leaders in urban sustainability: Alicia Daniels Uhlig (International Living Future Institute), Hillary Brown, FAIA (City College of New York Spitzer School of Architecture; author, Next Generation Infrastructure), and Warren Karlenzig (Common Current; author, How Green Is Your City?). Hosted by Post Carbon Institute’s Daniel Lerch (author, Post Carbon Cities), in this webinar we’ll explore the findings of the new Island Press book Our Renewable Future: Laying the Path for One Hundred Percent Clean Energy—and what the implications are for community planning and design in the 21st century.

Community Resilience in an Era of Upheaval: Lessons from Richard Heinberg and Rebecca Wodder

Tuesday, February 27, 2018 3:00PM – 4:00PM EST

Join Island Press and Post Carbon Institute for a webinar featuring Richard Heinberg and Rebecca Wodder, contributors to The Community Resilience Reader. Richard, co-author of Our Renewable Future and Senior Fellow of Post Carbon Institute, will explain the intersections of our multiple sustainability crises. He will also discuss the six foundations for building community resilience. Rebecca, former President of American Rivers and current Chair of the Board of River Network, will share examples of resilient systems that better address issues of water at the community level. The webinar will be moderated by Daniel Lerch, Education & Publications Director for Post Carbon Institute and editor of The Community Resilience Reader.

Download the PowerPoint presentation of key takeaways, figures, and images for Our Renewable Future.

Download the images, graphs, and tables from the book here. These are for educational, noncommercial purposes only.

Around the world, renewable energy is making headlines: last month, clean energy supplied almost all of Germany’s power demand for one day, while Portugal ran entirely on renewable energy for 107 hours straight. Countries agree that we need to transition to a renewable world. The question is how will this look and feel, and how do we get there? Our Renewable Future examines the challenges and opportunities presented by the shift to renewable energy and explains why a clean energy future cannot happen by simply adding more solar panels and wind turbines. In the same way that our current “normal” is fundamentally different from that of the preindustrial world, we must reimagine our future at a profound level, and adapt our energy usage as dramatically as we adapt our energy sources.

Check out Chapter 1 from the book below.

This post originally appeared on PostCarbon.org and is reposted with permission.

I spent the last year working with co-author David Fridley and Post Carbon Institute staff on a just-published book, Our Renewable Future. The process was a pleasure: everyone involved (including the twenty or so experts we interviewed or consulted) was delightful to work with, and I personally learned an enormous amount along the way. But we also encountered a prickly challenge in striking a tone that would inform but not alienate the book’s potential audience.

As just about everyone knows, there are gaping chasms separating the worldviews of fossil fuel promoters, nuclear power advocates, and renewable energy supporters. But crucially, even among those who disdain fossils and nukes, there is a seemingly unbridgeable gulf between those who say that solar and wind power have unstoppable momentum and will eventually bring with them lower energy prices and millions of jobs, and those who say these intermittent energy sources are inherently incapable of sustaining modern industrial societies and can make headway only with massive government subsidies.

We didn’t set out to support or undermine either of the latter two messages. Instead, we wanted to see for ourselves what renewable energy sources are capable of doing, and how the transition toward them is going. We did start with two assumptions of our own (based on prior research and analysis), about which we are perfectly frank: one way or another fossil fuels are on their way out, and nuclear power is not a realistic substitute. That leaves renewable solar and wind, for better or worse, as society’s primary future energy sources.

In our work on this project, we used only the best publicly available data and we explored as much of the relevant peer-reviewed literature as we could identify. But that required sorting and evaluation: Which data are important? And which studies are more credible and useful? Some researchers claim that solar PV electricity has an energy return on the energy invested in producing it (EROEI) of about 20:1, roughly on par with electricity from some fossil sources, while others peg that return figure at less than 3:1. This wide divergence in results of course has enormous implications for the ultimate economic viability of solar technology. Some studies say a full transition to renewable energy will be cheap and easy, while others say it will be extremely difficult or practically impossible. We tried to get at the assumptions that give rise to these competing claims, assertions, and findings, and that lead either to renewables euphoria or gloom. We wanted to judge for ourselves whether those assumptions are realistic.

That’s not the same as simply seeking a middle ground between optimism and pessimism. Renewable energy is a complicated subject, and a fact-based, robust assessment of it should be honest and informative; its aim should be to start new and deeper conversations, not merely to shout down either criticism or boosterism.

Unfortunately, the debate is already quite polarized and politicized. As a result, realism and nuance may not have much of a constituency.

This is especially the case because our ultimate conclusion was that, while renewable energy can indeed power industrial societies, there is probably no credible future scenario in which humanity will maintain current levels of energy use (on either a per capita or total basis). Therefore current levels of resource extraction, industrial production, and consumption are unlikely to be sustained—much less can they perpetually grow. Further, getting to an optimal all-renewable energy future will require hard work, investment, adaptation, and innovation on a nearly unprecedented scale. We will be changing more than our energy sources; we’ll be transforming both the ways we use energy and the amounts we use. Our ultimate success will depend on our ability to dramatically reduce energy demand in industrialized nations, shorten supply chains, electrify as much usage as possible, and adapt to economic stasis at a lower overall level of energy and materials throughput. Absent widespread informed popular support, the political roadblocks to such a project will be overwhelming.

That’s not what most people want to hear. And therefore, frankly, we need some help getting this analysis out to the sorts of people who might benefit from it. Post Carbon Institute’s communications and media outreach capabilities are limited. Meanwhile the need for the energy transition is urgent, and the longer it is delayed, the less desirable the outcome will be. It is no exaggeration to say that the transition from climate-damaging and depleting fossil fuels to renewable energy sources is the central cause of our times. And it will demand action from each and every one of us.

Two of the country’s leading energy experts spoke at the SPUR Urban Center in San Francisco, California on June 2, 2016 to discuss renewable energy. David Fridley, a staff scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Richard Heinberg, a Senior Fellow-in-Residence at the Post Carbon Institute, discuss the unsustainable energy system and consumption in the U.S. The experts address the vast amounts of lost energy, financial debt, and the effect on the average consumer. Fridley and Heinberg have been studying renewable energy for decades and are taking a new approach to redefining the way we consume energy commercially and residentially. The two have written a new book, Our Renewable Future, which goes in depth into their research on renewable energy for a sustainable future.

Check out the recording on YouTube or watch below.

In early May of this year, Portugal ran on renewable electricity alone for four consecutive days. And later that same month, on May 15, Germany filled almost all its electricity needs with solar, wind, and hydro power.

This is good news: it tells us we’re making progress toward a zero-carbon energy system. But it also helps us see the challenges to a full renewable energy transition.

Many press reports said Portugal and Germany were getting all their energy from renewables during these short periods of abundant wind and sunlight. But it’s important to remember that we’re really talking only about electricity, which currently represents about 20 percent of global final energy usage. The other 80 percent of energy usage occurs mostly in transportation, agriculture, industrial processes, and in heating buildings, and currently requires liquid, gaseous, and solid hydrocarbon fuels. We have a big challenge ahead of us in electrifying those areas of energy usage.

In Germany on May 15, power prices turned negative several times during the day: utilities were effectively paying consumers to use electricity. This points to the existential crisis that renewables pose for conventional utilities—which, after all, need to sell power to pay for their sunk costs (grid infrastructure and power plants) and for the conventional fuels they still use. What can they do when there’s just too much sun and wind? The sensible response would be to store the energy for later, but that implies still more infrastructure costs.

During many days in the year Portugal and Germany face a situation opposite from the one they encountered in May: there is no wind or solar power to speak of. Then conventional coal, gas, or nuclear power plants are still needed—and will be until a time in the future when there is enough storage and redundant capacity in place to buffer the intermittent availability of sun and wind. But getting there will require both investment and a restructuring of the economics of the power industry.

As co-author David Fridley and I conclude in our book Our Renewable Future, the renewable energy transition will not consist of a simple process of unplugging coal plants and plugging in solar panels or wind turbines; it will imply changes in how we live, how much energy we use, and when we use it. Historic energy transitions (the harnessing of fire, the advent of agriculture, the fossil fuel revolution) changed societies from the bottom up and from the inside out. There’s no reason to assume the renewable energy revolution will be any less transformative.

Around the world, renewable energy is making headlines: last May, clean energy supplied almost all of Germany’s power demand for one day, while Portugal ran entirely on renewable energy for 107 hours straight. We asked some of our authors how these accomplishments will affect the way other countries think about renewable energy, and what this means for the US. Check out what they had to say below.

Renewables are already being taken seriously by the marketplace, but ultimately it’s a matter of economics: fossil fuels don’t pay their true cost—including the costs associated with emissions of carbon dioxide and other pollutants—and so it’s not a level playing field. A carbon tax (like the Yeson732.org carbon tax effort I’m part of that will be on the ballot in Washington State in November) would help internalize those external costs and give a boost to renewables and conservation. It’s still going to be a long time before the USA operates entirely on renewables for a day or more—it’s a big country and we’ve got a lot of coal and natural-gas power plants—but the sooner we start moving in that direction the better!

-Yoram Bauman, author The Cartoon Introduction to Climate Change

It is great to see these milestones achieved, but I think even more important climate policy and achievements are now starting to be seen on the horizon. There is a new wave of policymaking focused on 80 percent or even complete decarbonization of energy by 2050, travelling far beyond the 2030 date in most official goals and plans, including the U.S. Clean Power Plan. While the 2050 works are in their early stages, and most are closer to visioning exercises than actionable plans, this is the next phase of planning and operations for no-carbon energy. Thirty-five years is a very long time to plan forward, but it is within the life span of many large energy technologies and nearly all of the buildings that are in existence today. Every year we move towards 2050 we lock in more of the system that will be in place, or already retired, by that year, so it’s really the right time to start working on this. Almost makes you want to start singing that old Fleetwood Mac song, the theme of Bill Clinton’s first presidential campaign. Google it, you twenty-somethings.

-Peter Fox-Penner, author Smart Power Anniversary Edition

Many press reports said Portugal and Germany were getting all their energy from renewables during these short periods of abundant wind and sunlight. But it’s important to remember that we’re really talking only about electricity, which currently represents about 20 percent of global final energy usage. The other 80 percent of energy usage occurs mostly in transportation, agriculture, industrial processes, and in heating buildings, and currently requires liquid, gaseous, and solid hydrocarbon fuels. We have a big challenge ahead of us in electrifying those areas of energy usage. Continue reading Richard's full post here.

-Richard Heinberg, co-author Our Renewable Future

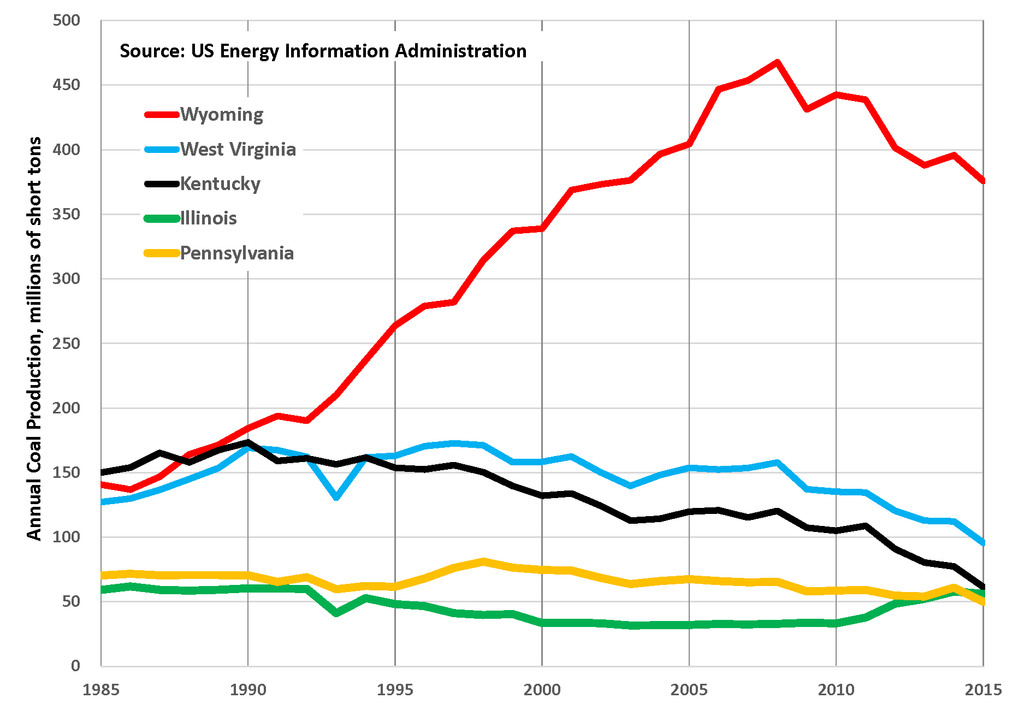

During the second presidential debate on October 9, Republican presidential nominee (now President-Elect) Donald Trump claimed that “clean coal” could meet the energy needs of the United States for the next 1,000 years. Now that Mr. Trump will be in the position of making national energy policy, it’s worth examining that assertion.

First, does our nation really have 1,000 years’ worth of coal? No official agency thinks so. The U.S. Energy Information Administration estimates United States coal reserves at 477 billion short tons, a little over 500 years’ worth. But this calculation is probably highly misleading. A 2007 study by the National Academy of Sciences criticized the history of systematically inflated national coal reserves figures, while still allowing that, “there is probably sufficient coal to meet the nation’s coal needs for more than 100 years.” Still other studies ratchet that “100 years” down much further.

In 2009 I spent several months reviewing the available data and studies; the results were published as the book Blackout, which concluded that there is a strong “likelihood of [global coal] supply limits appearing relatively soon—within the next two decades.”

The U.S., China, Britain, and Germany have all already mined their best coal resources; what remains will be difficult and expensive to extract. Coal production from eastern states (West Virginia, Tennessee, Ohio, Pennsylvania) has been on the skids for decades as a result of the depletion of economically minable reserves. The focus of the industry’s efforts has therefore largely shifted to Wyoming, but production there is now waning as well. A 2009 study by Clean Energy Action, a citizen group in Boulder, Colorado, confirmed that Wyoming and Montana hold a large portion of remaining U.S. coal reserves, but also concluded that 94 percent of reserves claimed by the mining industry and the U.S. Energy Information Agency are too expensive to extract. It’s probably safe to say that there are sufficient supplies of coal there and in the rest of the U.S. to permit mining to continue for decades into the future—but only at a declining rate.

In short, from a supply standpoint alone, the idea of 1,000 years of coal—enough to supply all of our energy needs for a millennium—is so exaggerated as to be laughable.

Does attaching the word “clean” to the word “coal” somehow change that picture? Hardly. For years, Americans have seen billboards and TV commercials touting “clean coal,” while politicians on both sides of the aisle have extolled its promise. The technology to capture carbon emissions from coal-fired power plants has been tried and tested. Yet today almost none of the nation’s coal-fueled electricity-generating plants are “clean.”

Why the delay? The biggest problem for “clean coal” is that the economics don’t work. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is extremely expensive. That gives the power industry little incentive to implement it in the absence of a substantial carbon tax.

Why would implementing CCS be so expensive? To start, capturing and storing the carbon from coal combustion is estimated to consume 25 percent to 45 percent of the power produced, depending on the approach taken. That translates to not only higher prices for coal-generated electricity but also the need for more power plants to serve the same customer base. Other technologies designed to make carbon capture more efficient aren’t commercial at this point, and their full costs are unknown.

And there’s more. Capturing and burying just 38 percent of the carbon released from current U.S. coal combustion would entail pipelines, compressors and pumps on a scale equivalent to the size of the nation’s oil industry. And while bolting CCS technology onto existing power plants is possible, it is inefficient. A new generation of plants would do the job much better—but that means replacing roughly 600 current-generation power plants.

Altogether, the Energy Department estimates that wholesale electricity prices with the initial generation of CCS technology would be 70 percent to 80 percent higher than current coal-based power—which is already uncompetitive with natural gas, wind, or even new solar PV installations.

The price per kilowatt-hour of electricity produced from solar and wind power is steadily dropping, with no bottom in sight. The only thing that keeps coal-based electricity even in the ballpark of prices for renewable energy sources is the industry’s ability to shift coal’s hidden costs—environmental and health damage—onto society at large. If climate regulations eventually kick in and the coal power industry adopts CCS as a survival strategy, the task of hiding from the market the real and mounting costs of coal can only grow more daunting.

The problem is that coal just isn’t “clean.” CCS won’t banish high rates of lung disease, because it doesn’t eliminate all the pollutants from the combustion process or deal with the coal dust from mining and transport. It also doesn’t address the environmental devastation of “mountaintop removal” mining.

By the time we transitioned the nation’s fleet of coal-burning power plants to CCS (which would take three or four decades), the nation’s coal production would be supply-constrained as a result of ongoing depletion. Let’s face it: the coal industry is dying. If Mr. Trump wants to put the industry on life support by subsidizing it somehow, he will only delay the inevitable, while spending money uselessly to do so.

In all likelihood, our real future lies elsewhere—with distributed renewable energy and a planned substantial reduction in overall energy usage through efficiency measures and a redesign of the economy. The inevitable transition away from fossil fuels will constitute a big job, and it only gets bigger, harder, and more costly the longer we delay it. Claiming that it makes sense to return to coal at this late date is delusional for economic as well as environmental reasons.