Urban Bikeway Design Guide, Second Edition

260 pages

8.25 x 10.75

75 photos, 100 illustrations

260 pages

8.25 x 10.75

75 photos, 100 illustrations

The NACTO Urban Bikeway Design Guide, Second Edition, is based on the experience of the best cycling cities in the world. Completely re-designed with an accessible, four-color layout, this second edition continues to build upon the fast-changing state of the practice at the local level. The designs in this book were developed by cities for cities, since unique urban streets require innovative solutions.

To create the Guide, the authors conducted an extensive worldwide literature search from design guidelines and real-life experience. They worked closely with a panel of urban bikeway planning professionals from NACTO member cities and from numerous other cities worldwide, as well as traffic engineers, planners, and academics with deep experience in urban bikeway applications. The Guide offers substantive guidance for cities seeking to improve bicycle transportation in places where competing demands for the use of the right-of-way present unique challenges.

First and foremost, the NACTO Urban Bikeway Design Guide, Second Edition will help practitioners make good decisions about urban bikeway design. The treatments outlined in this updated Guide are based on real-life experience in the world's most bicycle friendly cities and have been selected because of their utility in helping cities meet their goals related to bicycle transportation. Praised by Former Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood as an “extraordinary piece of work,” the Guide is an indispensable tool every planner must have for their daily transportation design work.

"The Urban Bikeway Design Guide, now in its second edition, is positioned as the go-to resource for planners that are designing bike infrastructure in North America."

Momentum Mag

"This is an extraordinary piece of work that's long overdue."

Ray LaHood, former United States Secretary of Transportation

"The guide will serve as an essential blueprint for safe, active, multi-modal streets."

Gabe Klein, former Chicago Transportation Commissioner

"NACTO's Urban Bikeway Design Guide gives American planners and designers the tools they need to make cycling accessible to more people."

Janette Sadik-Khan, former New York City Transportation Commissioner

"A Must-read… Landscape architects, planners, and city officials should find this guide invaluable. Anyone who advocates for increasing bicycle infrastructure in our cities will find many useful tools for implementing best practice infrastructure."

ASLA's The Dirt

Posted by Eric Katz at the Green Mobility Network

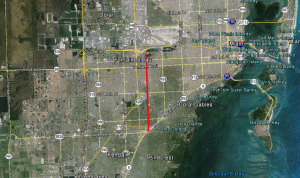

Friends of the Ludlam Trail (FOLT) is a flagship campaign of Green Mobility Network that brings together a coalition of bicycle and pedestrians advocates, conservationists, public health professionals and community leaders that seek to convert an abandoned 6.2 mile long, 100 foot wide railway that cuts through the heart of Miami-Dade County, and transforms it into a world class linear park and trail.

Friends of the Ludlam Trail (FOLT) is a flagship campaign of Green Mobility Network that brings together a coalition of bicycle and pedestrians advocates, conservationists, public health professionals and community leaders that seek to convert an abandoned 6.2 mile long, 100 foot wide railway that cuts through the heart of Miami-Dade County, and transforms it into a world class linear park and trail.

In the 1920s, railroad tycoon, developer and pioneer Henry Flagler constructed the railroad infrastructure that sparked that development that transformed South Florida into the bustling metropolis it is today. Over the course of the 20th century, particularly post WWII when the auto centric American Dream began to sweep the country, many of Flagler’s railroads were disassembled, and or reconstructed into expressways, light rail systems, bus ways, or simply left abandoned. One particular abandoned railway, known then as the “Oleander Trail” was part of Flagler’s south Florida network known as the Miami Belt Line. Over time the corridor would become an important regional anchor, attracting a series of major development projects including Miami International Airport, industrial parks, regional shopping malls, office buildings, schools, parks and plenty of low density subdivisions. Over time the frequency of freight trains along the corridor decreased, and the current owner, Florida East Coast Industries, formally abandoned the property in 2006. Today, the Ludlam Trail corridor is surrounded by 30,000 Miami-Dade residents living within a half mile distance.

Figure 2: The Ludlam Trail directly connect to 5 schools, 4 parks, 2 transit hubs and multiple shopping destinations

Figure 2: The Ludlam Trail directly connect to 5 schools, 4 parks, 2 transit hubs and multiple shopping destinations

Since then traffic congestion for the 3.5 million people living in Miami-Dade County has worsened to a state-of-emergency. Miami’s lack of planning, abundant levels of sprawl and poor bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure have made Miami one of the most unsafe places to bike or walk in the country. The Ludlam Trail corridor stands poised to make a substantial contribution, both to our countywide open space needs, but also providing equitable access to safe transportation options for thousands of residents. Remnants of the rail line remain with a raised berm and train artifacts randomly scattered along the corridor. Native trees, shrubs and wildlife have slowly reclaimed the land, which now serves as a sanctuary to native endangered plants and numerous birds, mammals, and insects.

Since the rail was disassembled, there have been various studies performed regarding what this stretch of land could eventually become. Due to its close proximity to thousands of people’s homes, anything proposed has always been a delicate and complex matter with neighbors ready to strike down any possibility of impacting their property or quality of life. The one idea that captured the hearts and minds of the community is the idea of a world class linear park and trail. About 10 years ago, Miami-Dade County produced Ludlam Trail design guide in the event that resources would one day be available to purchase the property. Its direct connection to 5 schools, 4 parks, 2 transit hubs and multiple shopping destinations make it a natural choice for improved connectivity. For years the Ludlam Trail idea remained a wild idea that would never actually get done in Miami. In 2013, Green Mobility Network, led by Chairman Tony Garcia, sought to reignite the Ludlam trail conversation. They established regular communication and partnerships with the community, and reached out to passionate neighbors. At the same time, Flagler/FECI had started the process of redeveloping the corridor as multifamily housing, a far cry from the linear park that the community was expecting. Because no formal planning process was established for conversion of an old rail line into a trail (or residential development), there was little opportunity for people in the community to weigh in on the development proposal. Before Flagler/FECI could perform any large-scale development, they had to pursue a land use change for the corridor which required a public vote from numerous community councils, and eventually the Miami-Dade County commission. Initially Flagler/FECI offered the community a proposal to have mixed-use development project along 75% of the entire 6 mile corridor, while leaving 25% (approximately 25 feet) open to the construction of a future trail (not paid for or maintained by Flagler/FECI). Green Mobility Network, along with our thousands of supporters and members were not in favor of this plan.

Through the power of thousands of residents and hundreds of concerned volunteers, GMN launched a grassroots campaign aimed to mobilize support for the Ludlam Trail and demand a fair public process regarding the future of a piece of land that would carry massive regional impact for Miami today, and in the future. Through funding from Rails to Trails, The Miami Foundation, and individual donations, thousands of flyers and petitions were distributed to get the word out. Beyond traditional methods, the internet and social media was a central part of the Friends of Ludlam Trail campaign built, with a strong presence on its website blog, Facebook, Twitter and You Tube channels. It didn’t take much to pack auditoriums, school cafeterias and commission chambers demanding a fair public process. Due to enormous pressure from the people and local media, Flagler/FECI withdrew their proposal and agreed to have the county adopt the application and begin a formal charrette process with the goal of finding a win-win solution.

Through successful campaigning and negotiating and a fair public process between the land owners, Miami-Dade County government and the community, Green Mobility played a central role in ensuring that a majority of the corridor was preserved as open space. We are happy to report that the latest consensus plan preserves 75% of the corridor to green space, and 25% to development. Further, no development is to occur behind any land adjacent to people’s homes, commercial and industrial zones only.

The campaign to construct the grand vision of the Ludlam Trail continues. There are still many challenges ahead, but we have already shocked numerous doubters who didn’t think getting this far was even possible. The search for funding stands as our number one objective. Green Mobility Network and the community must now advocate for funding towards the acquisition, design, construction and maintenance of the trail. Green Mobility Network is tremendously proud of its Friends of the Ludlam Trail Campaign. Our board and steering committees are eternally thankful for the long list of community partners, organizations, businesses, elected officials and residents we have worked together with throughout this campaign. This next year will be the most important as we will be making numerous trips to Tallahassee to advocate for funding sources that would enable the Ludlam Trail vision to get built. While the projected cost is great, this pales in comparison to the enormous economic, social, and environmental impact this trail will have on the community. What makes our campaign truly special is that not only have we received a buy-in from the community, but Flagler/FECI has done an amazing effort at working closely with Green Mobility and the community to find the win-win scenario. When we advocate for funding, we will be doing so together with the developer.

The Ludlam Trail is already a noteworthy case study to anyone interested in learning more about the development of greenways in urban environments, but those passionate about this land feel that the story of the trail exudes a much deeper undertone worthy of recognition as a chapter in Miami’s history. Henry Flagler is the understood as the father of Miami, who even recommended the city’s name. His railroad and vision of Miami as a new American metropolis is the reason we have world class destinations such as Palm Beach, South Beach and Key West. Is it pure irony that our project brings us face to face with the legacy of what Miami used to be 100 years ago? As today’s society visualizes the NEXT 100 years of Miami, the vision is not nearly as grand. Fears regarding sea level rise, everglades degradation and pine rocklands fragmentation, paint a dark picture of a place still globally renowned today as a unique paradise. No matter what happens in the next 100 years, it’s an issue beyond the scale of what the Ludlam Trail can alone fix. However, the trail will definitely serve as an important symbol of what our generation did when we possessed the data, technology, communications and resources to scientifically project our immediate and long term futures.

It will take a village to make this project a success. Please join us as we fight to build a world class trail that our children, grandchildren, and we feel even Henry Flagler would be proud of!

Posted by Randy LoBasso of the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia ![Blocked bike lanes[thumbnanil]](http://bicyclecoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/blocked-13th-Street-bike-lanethumbnail-e1407352145923-1024x1024.jpg)

You tweeted, we listened. In November 2013, after beginning a dialogue with the Philadelphia Parking Authority about illegal vehicle parking in city bike lanes, we suggested the PPA embark on a social media campaign to hear citizen complaints directly. In December, that campaign—on Twitter, with the hashtag #unblockbikelanes—began. The goal was for PPA to gather information about problem locations to help the authorities discern their targeted potential ticket areas. There were hundreds of tweets dedicated to calling out parked cars and trucks obstructing bike lanes.

@bcgp @PhilaParking @PPAwatch Apparently safety is NOT CVS goal for cyclist.#unblockbikelanes pic.twitter.com/6Fzzqp9eTF — Jennifer Morrow (@atibamanii123) June 20, 2014

C'mon @PhillyPolice you can do better. It's rush hour. @PhilaParking. #unblockbikelanes pic.twitter.com/FBcyoRN4yQ

— Bike Coalition Phila (@bcgp) June 6, 2014

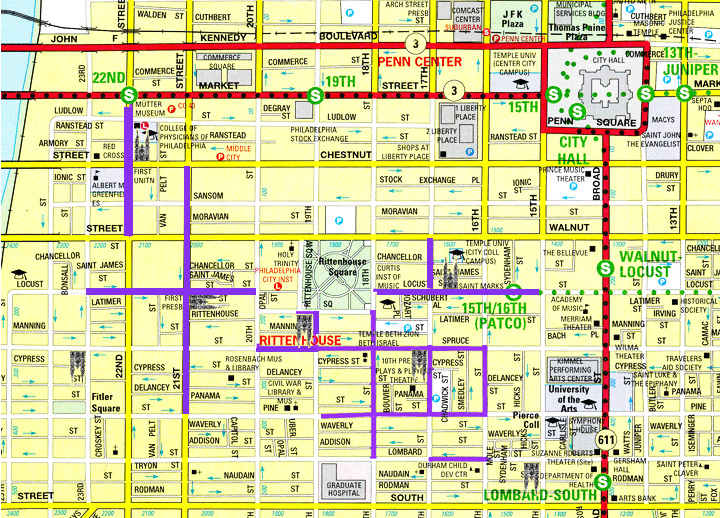

Now, several months later, the Bicycle Coalition has received enough raw data from PPA that we can come to certain conclusions about the enforcement of cars illegally parked in bike lanes. BCGP policy fellow Susan Dannenberg put together this awesome report on it. Important background information to bear in mind: According to Philadelphia Code, if a bike lane is adjacent to the curb (like Spruce and Pine), vehicles may not park—but they are allowed to unload/load people and goods. Commercial vehicles are permitted 20 minutes of loading on those streets. On streets like Baltimore Ave. and Fairmount Ave., where the bike lane is adjacent to cars, blocking the lane is considered double parking, and is illegal all the time. There’s a special understanding between Spruce and Pine religious congregations, the City, the Police Department, and the PPA that permits cars to park in the bike lanes on certain blocks during religious services on weekends. Lanes open for parked cars on Sundays are shown on the map below (in purple.)

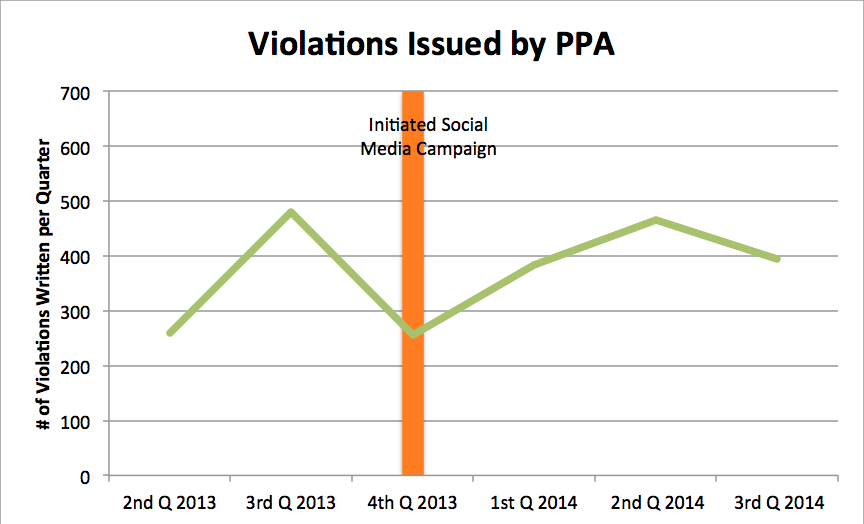

Our conversation with the PPA was ongoing throughout 2014. And the final analysis found that there was a slight uptick in tickets written in bike lanes (even though they fell off in the third quarter), as shown in the figure below.

What’s unclear is if behavior actually improved between the second and third quarter (and, therefore, there were less tickets to hand out) or if violations weren’t being enforced. Maybe the second quarter enforcement of vehicles in bike lane was just that good, but maybe the lack of momentum after the initial social media push led to a little slacking out of 8th and Filbert. That said, the social media campaign worked. It clarified which blocks are problem spots and which blocks received the most violations. And, there is a direct correlation between your tweets to the PPA and stepped up enforcement—so, if you were someone who took pictures of cars in bike lanes and tweeted them at the PPA, thanks, and keep it up. But it didn’t necessarily have a lasting effect. So, where do we go from here? Here are our recommendations to the PPA:

It’s desnudas versus New York City.

Somehow shapely underclad women who’ve body-painted scanty tops have become a crisis in the city, requiring the demolition of plazas being built to make Times Square civilized.

The mayor and police commissioner overreacted, blaming the paving stones for this offensive (to some) innovation in the age-old art of the busker. To separate tourists and pedestrians from their cash, you gotta get a gimmick, as Ms. Mazeppa said in the musical “Gypsy.” And painted breasts certainly got everyone’s attention.

But the reaction is of a piece with America’s fear of public space. In other countries, a town square, or boulevardized street with wide sidewalks and cafés, invites conviviality as people stroll, take coffee, or hang out. In America, we assume that any public space that is not cordoned off for some “useful” purpose can only become a refuge for criminals, the homeless, and the mentally unstable. (In many suburbs, even sidewalks are looked on with suspicion. )

The police commissioner has concluded that plazas—permitting louche idleness instead of puritanical destination-focused purposefulness—conjured the presence of nude women. The solution? “Removal” of the problem. It’s a knee-jerk reaction, but a common one, unfortunately.

The “problem” with public spaces is sometimes with the space, but mainly with our failure to gainfully employ people, who turn to public space to earn income. On Times Square, people push theater tickets, comedy clubs, tour busses. As cartoon characters, “naked” cowboys, and statues of liberty, they hustle tips from picture-taking tourists. Times Square is a buskerama. Which is absolutely in tune with its identity as the most commercial of public spaces. It would not be swarming with record millions if it was not fun. The allure is not the mall-style retail, but the mega-signage, which from time to time achieves dizzy heights of commercial nuttiness—but recently seems to have settled into a corporate coma.

Actually New York City is a model in many ways for the management of public space. Intimate plazas have been created out of little more than flower pots and paint. They work, they are actively managed, and they’ve proven very popular.

The City’s administration has come to its senses and will not demolish the plazas, which have cost millions to install. They are essential because there are many more people in the square than the inadequate sidewalks can handle, and accommodating them is a safety issue. With the excruciatingly length of the plaza construction project, much of the square has been torn up for years, leaving bottlenecks that are inhumane and unsafe.

A task force has been convened to address the desnudas, and sanity will probably prevail. (Though one idea, to cordon the desnudas, sounds even sillier than the designated prostitution zones found in Holland are.)

There are many ways to manage this problem (on a recent balmy afternoon there was not a painted breast to be seen), but resort to heavy-handed policing or to removal of the “offending” space is the kind of answer that destroyed peoples’ faith in cities through much of the 20th century.

In downtown Seattle last night, I saw the soft glow in the dark of Westlake Park’s evolution from a “little engine that could” to the real deal. The evolution, you may ask? A one-year experiment in private management of a public place, partially inspired by Bryant Park, a New York City example. Yet this particular darkness said, in effect, worry not, for this is just a Friday night off for the Downtown Seattle Association/Metropolitan Improvement District management scheme.

Another New York City example has recently been at least a bit under siege. Like Bryant Park, the conversion of Times Square to a pedestrian plaza has become a model for the American experience. In civic discussions around the country, it is touted as proof of the possible, a domestic shining light of how every city can recreate places for people. Who needs to cite to Mayor Jaime Lerner’s similar accomplishments in Curitiba, Brazil—or to evoke European forbears—when you have an American story for local consumption that easily translates to “why not here”?

So, whether panhandling, or other tourist-oriented aversions drove (no pun intended) a late summer New York re-examination of the pedestrian concept, a “return to what was” for Times Square risks unintended consequences for the rest of us. As Seattle’s Westlake example shows, we covet the emblems and icons of big cities that lead, and for many Americans, the lessons of New York ring truer than Las Ramblas of Barcelona ever will.

If New York slides backward, so may also a multitude of “engines that could” who need the confidence that feeds the Little Engine’s immortal words, “I think I can”.

|

| Image: New York Times. January 21, 1975. “Decision Awaited on Permanent Times Sq. Mall |

In a period of intensified fears about crime, loitering, and ne’er-do-wells, the mall was never built, but the idea persisted. Other pedestrian malls of the era, most acutely in declining downtowns, were plagued by the anticipated social ills of the Times Square projects, and many were restored to car traffic in the 1980s and 90s.

Our present era bears scant resemblance to the first wave of pedestrianization schemes, especially as our narrative of the city has shifted from white flight-fueled decline and delinquency to gentrification and nagging fears of inauthenticity. We find ourselves at a strange cultural moment, somewhere between James Rouse’s festival marketplace and Banksy’s Disma-land, forging a beguiling Vegas-Orlando hybrid of friendly-faced characters trolling the now nostalgia-laden steps of buskers and prostitutes. In some sense, these larger than life figures inhabiting the Times Square plazas have become the ultimate irony of our Disneyfied landscape, their frustrated costumes bearing witness to the latent anger of a city beleaguered by class warfare, as though Guiliani had encased the beggars in costumes to disguise the pervasive squalor.

The problem with Times Square is not, however, that it has spawned a latent seediness, or even its intensified Disneyfication. The problem is that the success of the project and the trajectory of the city should have given weight to a much, much more ambitious vision of Broadway as a whole and that De Blasio should have instigated such a proposal upon taking office. To relieve the pedestrian congestion of the square, why not expand the plazas permanently north to Columbus Circle and south to Herald Square, as originally envisioned in the early 1970s. By undertaking a more comprehensive plan and capital investment in Times Square’s future, the administration might have had the foresight to craft a proactive strategy under which they could build out, manage, and define a clear vision of the Square, rather than defaulting to a reactive defeatism. Those within the administration and the advocates for public plazas, bike lanes, and other transportation investments that have multiplied across the city must also press beyond the painted lines of incremental progress in the interest of securing their investments in concrete and curbs. These capital investments can move the city and its citizens beyond the misconception of a perennial transportation experiment towards a new and permanent paradigm for the public realm.